If you've ever run an A/B test, compared campaign results, or debated whether a new product concept "really outperformed" the old one - congratulations, you've already brushed up against the world of significance testing.

Now, before your eyes glaze over (I know - statistics isn't everyone's cup of coffee), let's strip away the jargon and focus on what matters to you as a marketer: when can you confidently say one result is truly better than another, and when is it just random noise?

That's where 1-tailed and 2-tailed tests come in.

Why Significance Testing Matters in Marketing

Imagine you just ran two digital campaigns:

Campaign A used emotional storytelling.

Campaign B focused on product features.

Campaign A's click-through rate (CTR) is 5.2%, while Campaign B's is 4.8%.

Looks like A wins, right?

Maybe. But what if the difference is just due to chance?

Significance testing helps answer that question. It tells you whether the difference between A and B is statistically meaningful - i.e., whether it's likely to hold true in the wider market, not just in this test.

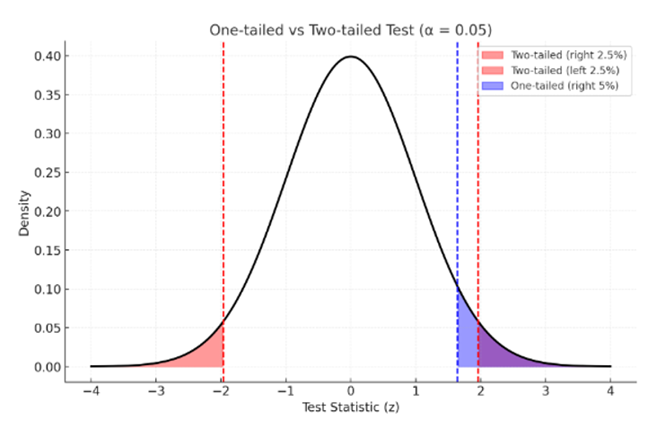

The Basics: 1-Tailed vs. 2-Tailed Tests

Here's the simple breakdown:

1-tailed test: You're testing if one thing is specifically better (or worse) than another.

2-tailed test: You're testing if there's any difference at all - could be better or worse.

Both start with the same question:

"Are A and B truly different, or is this just luck?"

But they differ in how specific you are about the direction of that difference.

When to Use a 1-Tailed Test

Use a 1-tailed test when you already have a clear directional hypothesis.

Example: You Expect One Version to Win

Say you're testing two email subject lines:

A: "Save 20% on Your Next Order"

B: "Your Exclusive 20% Discount Inside"

You believe version B will perform better because of the word "exclusive."

In that case, you're not interested if B performs worse - you only want to know if it performs better.

That's a 1-tailed test.

It's like saying:

"I only care if my new campaign outperforms the old one, not if it underperforms."

The advantage?

A 1-tailed test is more powerful in detecting improvement because it focuses only on one direction.

The caution?

If B actually performs worse, a 1-tailed test might not flag it as significant - because you never tested for that side of the outcome.

Example:

I once worked with a client who tested a new packaging design, convinced it would drive higher purchase intent. The 1-tailed test confirmed a significant lift - and they celebrated.

But when we checked the open-ended feedback, people actually disliked the new look!

The test had confirmed "significant improvement," but only because we weren't testing for potential decline.

Lesson: Only use 1-tailed tests when you're 100% sure the direction matters and the opposite outcome isn't important to you.

When to Use a 2-Tailed Test

A 2-tailed test is for when you want to know whether any difference exists, regardless of direction.

This is the default in most marketing and market research studies.

Example: Testing a New Concept or Product

Let's say you're introducing a new drink concept and want to compare it to your current best-seller.

You don't know yet whether people will like it more or less - you just want to see if there's a difference.

That's a perfect case for a 2-tailed test.

It's like saying:

"I just want to know if my new idea changes things, for better or worse."

Why It's Often the Safer Choice

Marketers love optimism - we want our new idea to work.

But a 2-tailed test protects you from bias by being neutral. It checks both sides of the story.

If A performs much better or much worse, you'll know either way.

Confidence Level: How Sure Are You?

Most marketers work with a 95% confidence level - meaning you're 95% confident your result isn't due to random chance.

Think of it like this: if you ran the same test 100 times, 95 of those times, you'd get a similar result.

That last 5%? That's the "it might just be luck" zone.

Sometimes you might want to tighten that up (say 99%) for big business decisions, or loosen it (90%) for exploratory tests where you just need a directional signal.

How It All Looks in Practice

Here's a simplified way to interpret your results:

Common Mistakes Marketers Make

1. Using the Wrong Test for the Question

I've seen teams use 1-tailed tests when they should've used 2-tailed ones - especially when comparing customer satisfaction scores or awareness levels.

If you don't know the direction, don't assume it.

2. Ignoring Sample Size

Even the best formula can't save you if your sample size is too small.

A test with 20 respondents per group isn't reliable - the difference could easily be random.

3. Over-Interpreting Small Differences

Just because something is "statistically significant" doesn't mean it's meaningfully significant.

For instance, a 0.5% lift in CTR may be statistically real but may not justify a campaign overhaul.

4. Forgetting the "Why"

Significance testing tells you that there's a difference, not why.

That's where qualitative feedback and deeper analysis come in.

Putting It All Together

Here's a simple rule of thumb you can remember:

If you care only about one direction (better or worse), use a 1-tailed test.

If you care about any difference, use a 2-tailed test.

For most brand, ad, and product research, 2-tailed is your go-to.

For conversion optimization or campaign tests where you're chasing a clear winner, 1-tailed can be a sharper tool.

Try It Yourself

We've built a simple Significance Test Calculator you can download - it handles both 1-tailed and 2-tailed tests.

Just plug in your results (% rates and sample sizes), choose your confidence level, and let Excel do the math.

It's a quick, marketer-friendly way to make sure you're not just chasing random differences - but making data-backed decisions you can trust.

Final Thought

In marketing, gut instinct will always matter - but when you can back it up with statistical proof, you're unstoppable.

Whether you're comparing ads, measuring lift, or defending a budget, understanding 1-tailed and 2-tailed tests turns your "I think" into "I know."

And that's how you go from guessing what works to proving what works.